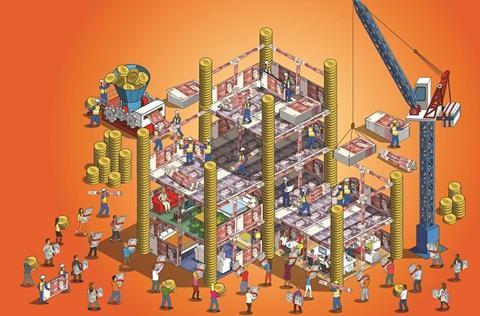

A combination of legislative changes, new technology and social shifts is changing how people invest in property.

The number of buy-to-let investors in the UK has increased from 702,000 in 2005 to around two million in 2017. This rapid growth has been driven by a mix of growing property prices, available and affordable debt and growing demand for rentals - in turn fuelled by people either buying to let or not selling homes as they move up the market.

The market has been slowed by the change to stamp duty in 2015, followed by tax changes in 2017. These were intended to rebalance the market and release more property so first-time buyers could get on the property ladder. But the changes negatively affect buy-to-let landlords who own property in their own names.

They can no longer offset all their mortgage interest against rent received and by 2020 they won’t be able to offset any. This will have an impact on the viability of holding these assets, especially for smaller owners.

Another factor set to have a major impact on the market is the implementation of the Retail Distribution Review (RDR) by the Financial Conduct Authority four years ago.

Starting before the buy-to-let market took off, there was a surge in the number of unlisted property funds, often accessed by individual investors via independent financial advisers (IFAs). The review cut off an important part of the distribution channel for many of these funds, as IFAs were unwilling or unable to carry on introducing clients to property funds.

Technology-led investment

After RDR, about a fifth of the 30,000 IFAs stopped advising clients whom they did not deem to have a large enough asset base. Research undertaken by Schroders found that 69% of those clients whom IFAs deemed unviable had less than £50,000 invested.

After the 2007 crash, a distrust of financial institutions led many to take their investments into their own hands, which explains the growth in buy-to-let. This wider change in attitudes has also led to people demanding far greater transparency from their investment professionals. Technology has helped with this, allowing people to log into their investment portfolios and get detailed information whenever they want it.

This has evolved further as the technology has got better. Ten years ago, one had to ring a stockbroker to make a trade and then wait to be posted an account summary. Now people are trading shares on their phones, with direct access to portfolio information. Crowdfunding has also allowed people with smaller sums of money to invest in larger assets, alongside others.

Find out more: Crowdfunding - a safe bet or a risk to avoid?

And, in the background, the automating of know-your-customer (KYC) requirements carried out by investment managers and banks has made it both easier for customers and cheaper for professionals to take on new clients. Automated KYC allows people to open a bank account on their phones, from beginning to end, with no need for hard copies. This reduces costs and creates a new world of products and services for customers.

People now manage their money and investments on their phones in the same way they order their Uber or Ocado shopping or buy flights or shoes. This massive, rapid social and technological shift over the past decade has transformed the way people invest in property and it is likely this shift is only the beginning of something far greater.

It will be interesting to see whether the large property fund managers with old legacy systems are able to adapt to the fast-changing demands and requirements of investors, or whether, like the banks, they are disrupted by fintech and proptech start-ups in this changing environment.

No comments yet