By Emanuela Barbiroglio

The rising tide of flood risk

Despite the huge costs incurred after the storms of the past decade, building in flood-risk areas is on the rise.

In Jane’s town in the South East of England, a residential scheme has just been completed. Ten new houses have been constructed on a former brownfield site and residents are set to move in soon. It looks like a dream development.

But there is a problem - a river just a few metres from the site, which while picturesque has a tendency to burst its banks, causing flooding. Worse, a nearby sewer is very old and has never been improved. Together, they could spell huge trouble.

Jane, who requested that neither her surname nor precise location be disclosed for fear of a fall in the value of her property, can see the new development from her home of 40 years. She can also keep an eye on the level of the river, which has forced her to vacate that home twice. The development in Jane’s neighbourhood is not an isolated example. Across England, developers are increasingly building on land with a high flood risk and councils are allowing them to do so.

The question is: why, when most experts agree that the number of severe weather incidents is only likely to increase?

Research by environmental data company Groundsure underlines the extent of the problem. Analysing figures from the Land Registry, the Department for Communities and Local Government and the Environment Agency, Groundsure found the proportion of properties being built in these high-risk flood zones had steadily risen from 7% in 2013-14 to 8% in 2014-15 and 9% last year.

“It was slightly surprising to see the high number of planning applications that have been granted [in areas] that are at risk,” says managing director Dan Montagnani. “We are very aware of the consequences of incidents and the damage they cause.”

Take the winter of 2013-14, for instance, when a series of storms hit the country. It was the heaviest rain recorded in 100 years and Defra estimated the total clean-up bill across England and Wales was between £1bn and £1.5bn. This summer also marks the 10th anniversary of the infamous summer of 2007, which was the wettest on record and saw 48,000 homes affected by flooding.

Ten years on, land and property expert Landmark Information commissioned a YouGov survey to investigate risk awareness. The research, published in June, revealed a general lack of knowledge about the issue, with 53% of respondents admitting they had never checked whether their home was in an area officially considered at risk of flooding.

Lack of knowledge

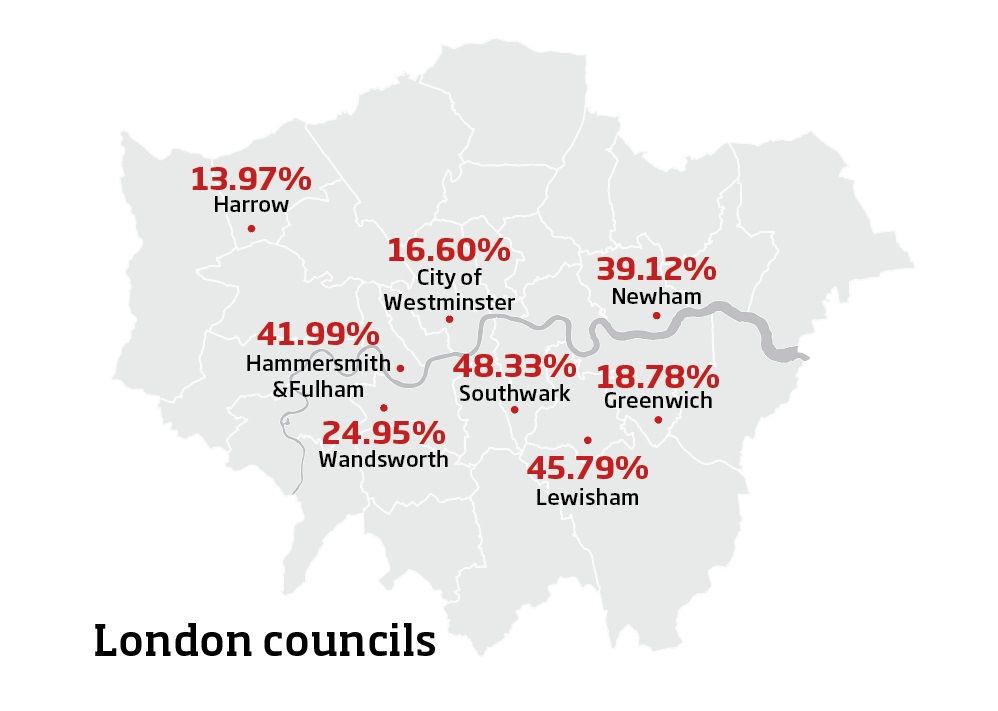

Yet historical data shows that the proportion of residential properties located in an area previously subject to a flood event was on average 5% per local authority in England and Wales. Moreover, a separate study conducted by Groundsure revealed that in some local authorities, a huge proportion of newly registered homes in 2015-16 were in Flood Zone 3 (FZ3) locations (where there is at least a 0.5% chance of a flood happening from the sea or a 1% chance from a river). Four London boroughs top the list: Southwark (48%), Lewisham (45%), Hammersmith and Fulham (42%) and Newham (39%). Outside London, Bury was the worst, with 39% of new homes built in high-risk areas in 2015-16.

Clearly, it is hard to avoid developing in FZ3 areas if these are the only sites available, as is often the case in London. Couple this with the fact that councils are being tasked with increasing housing supply and it is inevitable such sites will be developed. “Local authorities have a pressure on them to develop their land mass and they can’t get away from the fact that they are located in a flood plain,” adds Montagnani.

Another major issue is that flood risk tends not to rise up the political agenda until something goes wrong. “It’s the sort of thing that unfortunately only really gets political attention after there’s been a dramatic event,” says Guy Shrubsole, flooding campaigner for Friends of the Earth. “To be able to get an MP to pay attention at any other time of the year is extremely difficult.”

For their part, councils insist they are taking the necessary measures and only developing on flood-risk sites if absolutely necessary. In Dartford, for instance, where 8% of newly registered homes in 2015-16 were on previously undeveloped land in FZ3 areas, the borough council says it undertook a full review of its core strategy and that an ‘exception test’ was applied in line with national policy.

“In 2015-16, 83% of our residential development was on brownfield land,” says the borough’s planning policy manager Mark Aplin. “This is recognised in national policy as a very important aspect in deciding where housing can be located, and was considered alongside flood risk.

“We expect more than 95% of our 17,300 dwellings planned between 2006 and 2026 will be outside any flood risk or on brownfield land. The majority of the borough is metropolitan green belt: it is important that all sustainable development considerations are looked at in planning decisions.”

Councils also receive advice from the Environment Agency, which comments on all proposals for major development in areas at medium or high risk of flooding. It says that with the majority of such planning applications its advice is taken on board.

The agency adds that it is investing record amounts to reduce flood risk, spending £2.5bn nationally to protect more than 300,000 properties by 2021. “We would encourage everyone to know whether their home is at risk and sign up for our free flood warnings - 1.2 million people across the country are already signed up,” a spokesperson adds.

Risk assessment

Others are also trying to raise awareness. Mary Dhonau started the ‘Know your flood risk’ campaign in 2007 after her home was flooded. She has been trying to empower communities to take responsibility and minimise their collective flood risk.

“There is a presumption in favour of development due to the demand for housing, but insurance will not be available for new-build,” she says. “Building regulations must be changed to insist on flood-resilient measures being incorporated into the building process if this worrying trend continues.”

Dhonau lives in Worcester, where 4% of residential properties are within or very close to an area that has previously flooded, according to data from Landmark. The area now has a pumping station to alleviate the problem. However, she adds: “Like all areas at risk that have flood alleviation schemes, the risk has been reduced but not taken away.”

One effective approach may be to raise the lowest floors of properties above the expected flood level as Willmott Dixon did when it built on the flood plain in Wapshott, Staines. When the site - and most of the town - was badly flooded in 2014, all the properties remained safely above water.

“Where development is proposed in an area of flood risk, there is a need to work closely with the Environment Agency and the planning authority in

an open and collaborative relationship,” says Julia Barrett, director of sustainable development at Willmott Dixon. “The likely frequency and severity of flooding will determine the extent of measures, both passive and active, that will be required to mitigate the risk to an acceptable level.”

Mitigation measures include ensuring that the lowest levels of a property are used for storage, such as garaging, rather than living space, and fitting electricity meters above the potential flood level. Low-level toilets can also be fitted with backflow flaps to prevent inflow from the sewage system and fences and external walls can be designed to allow flood waters to drain away.

Countermeasures

The good news is the government is taking steps to counter the risk. Around £15m of natural flood management funding is being provided and floods minister Thérèse Coffey announced in July that a number of projects around the country had been allocated funding.

With new-builds, the key is ensuring that planning consents include robust mitigation requirements. “The solution could be a dialogue between all the people involved in the property market and the information being shared among everybody - not just the developers and the planners, but also the buyers and insurance companies,” says Montagnani.

Clearly, action needs to be taken to ensure that today’s new homebuyers don’t inadvertently find themselves in Jane’s position once a developer has handed over the keys and walked away.