In the days following the Brexit vote, commentators were quick to talk up the possibility of companies in the UK upping sticks and moving to cities in Europe.

Frankfurt, Berlin, Paris and Dublin were mentioned as likely beneficiaries, and Property Week duly visited them all to assess their prospects.

Now, however, another name has entered the fray: Amsterdam. It may not be the seat of government, but the Dutch capital’s credentials are strong. The city boasts a highly educated workforce, enviable public transport infrastructure and, crucially for multinational businesses, high levels of spoken English.

No wonder then that many commercial property experts are starting to wonder if Amsterdam might yet turn out to be a big beneficiary of Brexit. So how realistic are those expectations? And is Amsterdam’s property market prepared to welcome London’s economic refugees?

While no deals have been done to date, agents in Amsterdam report that they have had numerous enquiries from UK firms considering relocating to the city and Thomas van der Heijden, general manager of Dutch commercial agency DRS, says that enquiry numbers are growing. “We are advising a few parties,” he says. “A lot of them will move if they have a product that they want to market in Europe. Right now there’s a lot of risk analysis taking place.”

Eelco Hoet, regional director and head of corporate solutions at JLL Netherlands, agrees, adding that it is only a matter of time before the first big letting deal goes through. “We have had numerous discussions with clients, particularly those that have headquarters functions in the UK. Most will wait until a lease event is coming up before they make a decision but it is definitely a consideration. We have had discussions with three large international institutions about what to do next.”

The types of businesses actively considering taking space in Amsterdam include big financial services firms and major tech firms such as Facebook and Twitter. According to Juul Klumpes, partner at Knight Frank-associated company NL Real Estate, Google is currently on the hunt for around 6,000 sq m [64,580 sq ft].

“City centre rents are going up, but compared with London they are still reasonably low,” he says. “We’re seeing more tech companies expanding. There is very good connectivity in Amsterdam. There is also more interest from financial companies moving their EMEA head office from London to Amsterdam.”

It’s not just occupiers who are waking up and smelling the tulips. Investors too are increasingly interested in Amsterdam. “Because of the uncertainty in the UK due to Brexit, investors prefer to spend their money in the Netherlands because they don’t know what is going to happen [in the UK], especially as the pound has devalued over the last couple of months,” says Klumpes. “They don’t know what it’s going to bring politically.”

Investment boom

Indeed, while on the lettings side there’s only been talk, on the investment side there have been notable deals. The Bank of Tokyo and pensions giant Chesnara have both cited Amsterdam as a potential alternative location to London and this April, asset management company Marathon acquired a portfolio of commercial properties in the Netherlands from Credit Suisse for €380m.

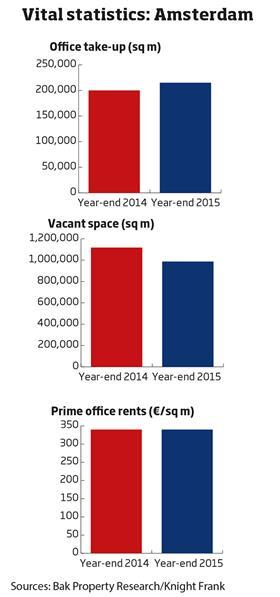

According to Savills World Research, Dutch commercial real estate investment volumes totalled €2.5bn in the first four months of 2016, a 47% increase on the same period last year.

Whether that jump can be ascribed to Brexit or just reflects a cyclical cooling of the London property market is unclear. What is certain is that Amsterdam’s popularity as an investment location is growing.

“We have seen investment volumes in London subside, whereas Dutch office investment YTD figures are well above their 2015 levels,” says Michael Hesp, head of Dutch strategy and research at CBRE Global Investors (CBRE GI). “With around 85% of the volume being cross-border capital, Amsterdam is a destination that international investors are looking at favourably.”

However, there is a cloud on the horizon. While less of an issue for investors, dwindling supply of office stock in Amsterdam is increasingly problematic for firms looking to locate in the city.

“There is still prime stock available, but it is drying up in the city centre,” says Klumpes. “A good sign is that the cranes are back and new developments are on the way. There’s movement in the market, but it’s not what it used to be two years ago, where you could have a pick of offices. We’re at a turning point. It used to be a tenant’s market - now it’s on its way to becoming a landlord’s market, especially in the areas within the direct vicinity of a train station.”

Hesp says that the lack of office space has prompted CBRE GI to tweak its Dutch Office Fund strategy so that it also invests in new-build projects. “There is not much vacant old stock left anymore,” he says. “For that reason, CBRE Dutch Office Fund now invests in development projects on prime locations that we secured years ago, taking some leasing risk, which we believe is very manageable because of the prime location.”

Projects include NoMA House, comprising 12,892 sq m of office space and 625 sq m of retail space, in the Zuidas district. Outside the city centre, where a post-recession wave of refurbishing office buildings into housing or hotels has tightened the market, the Zuidas area is the next prime district for lettings.

According to Hesp, however, much of the prime rental is already leased out, so tenants and investors are expanding their scope to next-tier markets such as Amsterdam Arena, Amsterdam Sloterdijk, Utrecht and Rotterdam.

Part of the problem is that securing planning permission for large commercial schemes in Amsterdam is difficult. OVG Real Estate was ultimately successful with The Edge, a 40,000 sq m office scheme and one of the most sustainable commercial buildings in the world, but the developer’s brand director, Cees van der Spek, describes building in the city as “almost impossible”.

“When attempting to build speculatively, developers like us have to prove to the government that the building is fully let pre-construction before they’ll allow us to go ahead,” he says. “They like you to come to them with tenants, but it makes it almost impossible to build new office schemes. Finding the land is difficult too - the government is taking its time releasing it to the market.”

Deadline approaching

Time is of the essence if the right stock is going to be in place to take advantage of firms leaving London when Brexit actually happens. “We’ve been told Brexit will take place in 2019,” says van der Spek. “I’m not sure how keen the government is to start building now, but if they don’t do it soon, office space won’t be available should London-based companies want to move to Amsterdam.”

Of course, Amsterdam isn’t just attractive to UK-based companies. As the lack of supply demonstrates, both domestic and international companies have been setting up shop in the city. Add to the mix a recent trend for converting city centre offices into hotels and commercial rents are only going in one direction.

“Brexit or not, the rental price is going up and that’s not necessarily a good thing,” says DRS’ van der Heijden. “Being expensive can be a disadvantage as it blocks new start-ups, and that’s happening a little bit in the city. I would tell the Amsterdam municipality to slow down with the transformation of offices into housing or hotels, because if it becomes too expensive we will chase businesses out of the area.”

If lack of stock and rising rents weren’t enough for incoming companies to contend with, Amsterdam also has a serious housing shortage. And as with commercial space, it isn’t clear whether the municipality will be able or willing to build enough new homes.

“If UK-based organisations considered coming to Amsterdam, the city probably wouldn’t be able to accommodate them,” says Hoet. “There is also the same issue with residential. Young people in particular would like to live in Amsterdam, but it’s very difficult to find a nice place. Employees who could come over from London might be well paid, but it will still be difficult to find housing.”

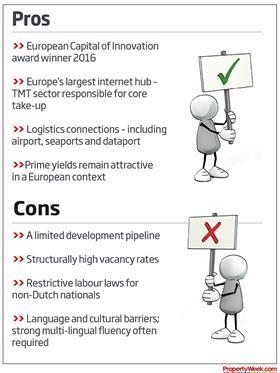

So Amsterdam enjoys many advantages and is already an attractive city for many international companies, but it also has its challenges. What’s more, issues such as the lack of offices aren’t about to be resolved overnight and rents will increase as a result, adding to the already sizeable relocation costs facing UK-based firms.

The lack of leasing deals indicates companies are adopting a cautious approach. If they’re to be in with a chance of securing decent space at a decent price they may need to get their clogs on.

No comments yet