Brexit could spell disaster for a construction sector already at crisis point in terms of manpower.

The message was unambiguous. “No more Polish vermin,” read the flyer shoved through letterboxes in Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, in the days following the EU referendum.

While the decision unleashed a wave of xenophobia across many parts of the country, it was met with only dismay in the housebuilding industry.

Companies up and down the land, but especially in London and the South East, recognise that migrants from eastern Europe in particular play a major role filling the industry’s skills and labour gap.

As Berkeley chairman Tony Pidgley put it before the vote: “London’s status as the world’s best big city is underpinned by labour mobility, cultural diversity and a constant influx of talent and investment from around the world. And the UK economy in turn is powered by the success of our capital city.”

The problem is that, following the victory of the ‘leave’ campaign, labour mobility looks set to be at least partly curtailed, with restrictions on freedom of movement high on the new government’s agenda in its discussions with the EU.

So just how dependent are housebuilders on EU migrant labour? And can the industry cope if freedom of movement is revoked?

Surge in migrant labour

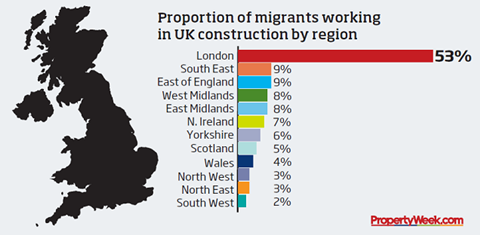

The answer to that first question is strikingly different depending on which part of the country you’re talking about, according to the National Institute for Economic and Social Research.

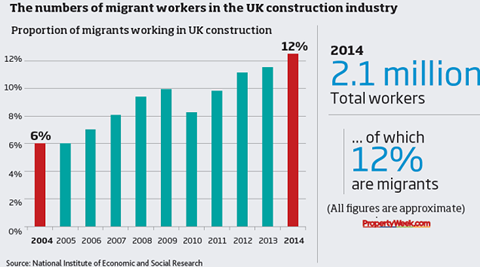

Nationally, in 2006 migrant labour accounted for 6% of the construction workforce, with EU citizens accounting for just 2%. But by 2014 the figures had increased markedly to 12% and 6% respectively.

However, as with so many things, London is essentially on a different planet to the rest of the country. In 2014, 54% of the construction workforce in the capital was foreign born, compared with 9% in the South East and east of England (the next highest proportion) and just 2% in the South West.

The surge in migrant labour, whether in London or nationally, is easily explained. As a result of the 2008 financial crash, thousands of skilled workers found themselves out of a job. Unlike previous cycles, however, most did not return to the industry.

Such was the length and depth of the downturn that they re-trained and went off to do other things. Then the housing market returned, supercharged by the launch of Help to Buy in 2013, and housebuilders were in the middle of a boom but without the workforce needed to keep pace with demand.

“Those people didn’t come back to the industry - they went off in a different direction,” says Simon Wilkins, founder of niche headhunter Face Fit.

“And then there was the market improving, so there was this double whammy: expanding build programmes but without the people. That hole had to be filled by people coming in from all over the place.”

While there is little hard evidence, the assumption is that the weight of migrant labour moved into the hottest markets.

“It’s heavily anecdotal, but those housebuilders that have more of their business in London report that they have more overseas labour in their workforce,” says Jim Ward, director of residential research and consultancy at Savills.

That tallies with experience on the ground. Mark Quinn is the founder of Kent-based developer Quinn Estates, which develops residential and commercial projects in the county. “Let’s say at the moment we employ 300 subcontractors on our sites,” he says. “Fewer than 30 of them are from Poland or Romania or other countries in the EU. In London it’s more like 50%. It might be less, but when I get on to a site in London a significant number of people are from eastern European countries.”

The 2008 crash and housing boom that followed explains a lot, but many housebuilders find that employing migrants is simply more convenient than spending vast amounts of time and cash training a new generation of British workers.

Part of that is down to work ethic. “Anybody moving to a foreign country has made a conscious decision to move for work and their attitude is likely to be more positive,” says Brian Green, a construction economist and commentator.

Another benefit of employing migrant workers is that they are more likely to be willing to move to where the work is, he adds: “One of the things about migrant labour is that it’s flexible, and by definition it’s ready to move. Construction by its nature is a mobile industry: people have to move where it’s happening or you have to create a new stock of labour locally.

“If you try and move [a British worker] from the North East, they’re going to want to be compensated. It’s easier to use migrant labour.”

So the industry, at least in the South East, is currently reliant on migrant labour. But there are signs that the big housebuilders are starting to take steps to nurture the next generation of domestic workers.

“There is a much bigger demand for UK workers,” says Wilkins. “If you look at companies’ jobs boards, you’ll find the odd key role, but largely it’s all apprentices. Everybody wants an apprentice for something - they’re trying to grow their own people.”

The surge in apprenticeships was evident well before 23 June and, according to Savills’ Ward, can be explained by an improvement in many eastern European economies, which has made a move to the UK far less appealing.

“Recently, it’s been harder to attract Polish workers because the Polish economy has been doing quite well,” he says.

Insufficient talent

While it is encouraging that the big housebuilders are investing in training British workers, apprenticeships take time - three to five years, depending on the trade.

It is unlikely, even in the longer term, that there will be sufficient domestic talent in the pipeline to meet demand, particularly if the industry is to get close to building the 250,000 homes per year most experts agree the country needs.

There will therefore be a continued need for the workforce to be supplemented by migrant labour. The question is how that aligns with the government’s promises to curb immigration.

Despite appearing to row back on former prime minister David Cameron’s pledge to cap annual immigration levels to the “tens of thousands”, the new prime minister has repeatedly promised that freedom of movement will be curtailed.

“We have a very clear message from the British people in the Brexit vote that they want us to bring in some control on free movement,” Theresa May recently told a press conference in Rome. “They don’t want free movement rules for movement of people from the EU member states into the UK to operate as they have done in the past. And we will deliver on that.”

So which political imperative will take precedence - cuts to immigration or building more homes? Many in the industry think a compromise can be reached that would allow the government to throw a bone to the anti-immigration lobby without damaging the UK’s growth prospects.

“The industry will always need a degree of migrant labour,” says Green. “The question is how much? It’s a political issue based around how much we’re prepared to spend on training and how much we’re willing to accept migrant labour. Clearly there is a balance.”

Others, however, take a stronger line, believing that, no matter the rhetoric, a business-friendly Conservative government won’t do anything that would act as a check on development.

“In terms of restrictions on labour, I think there will be, but I’ve also always thought there will be a political fudge,” says Quinn, quipping: “I think with the proposed points system… you’ll probably have to be able to breathe and have a heart rate in order to get in. That’s probably how they’ll deal with it.”

A Home Builders Federation (HBF) spokesman says that if and when freedom of movement is curtailed, the HBF will lobby to ensure a quota system is agreed so migrants can continue to support housing delivery.

“The government would be sympathetic - housing is a key commitment,” he says, pointing to the system that allows non-EU citizens to work in the NHS and the waiver scheme for Irish construction workers in place in the 1950s and 60s.

Quota system

The industry’s expectations may well be proved correct. As equities analyst and commentator Alastair Stewart puts it: “I’m sure if employers say they need these people that they’ll be allowed to hire them.” Wilkins says more bluntly: “I don’t think there will be any issues on movement - we’d be stupid as a country to do anything like that. We’d be shooting ourselves in the foot.”

Perhaps so, but with the anti-immigration lobby riding high post referendum and a government with a working majority of just 17, freedom of movement will continue to be a key political issue throughout the current parliament. What’s more, the industry’s hopes have been thwarted before: most went into June confident the great British public would vote to remain in the EU.

This week, a report by the Social Market Foundation warned that 590,000 EU nationals would not meet residency requirements and be forced to leave after Brexit. In short, there is a very real danger that the construction crisis will escalate if the great British public do not understand the crucial role played by migrant labour in housing delivery… or simply don’t care.

No comments yet