I am standing at a bus stop on Pimlico Road, just in front of the Chelsea Barracks site, together with a small crowd.

But this is not the usual bunch of commuters and tourists. They are journalists, cameramen and photographers from around the world. And we are at the meeting point for what is probably the strangest guided bus tour of London.

After a short wait the bus turns up; an innocuous coach with a sign fixed to the windscreen that reads ‘Kleptocracy tour - Nigeria’.

Kleptocracy Tours started in early 2016, when Roman Borisovich, a former banker-turned-anti-corruption campaigner, organised the first sightseeing of properties owned by foreign ‘kleptocrats’.

Borisovich is a massive man, with short blond hair and a thick Russian accent. He worked for 15 years in Wall Street and the City of London and is a supporter of and, more importantly, an adviser to Alexei Navalny, a Russian dissident blogger now considered the leading political opposition to president Vladimir Putin.

For the past two years, he has been doing in London what Navalny has been doing in Russia. Supported by a team of investigative journalists and researchers into money laundering, he tours the capital to expose the lavish properties bought with dirty money - the first tour focused on oligarchs from Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan. He has even set up an organisation called Committee for Legislation Against Moneylaundering in Properties by Kleptocrats (ClampK).

Our goal is to stop the avalanche of dirty money pouring into the UK, particularly London - Roman Borisovich, organiser

“Our goal is to stop the avalanche of dirty money pouring into UK real estate and particularly into central London,” he says as the bus sets off.

The focus of the tour is on high-profile political figures who own London property. An estimated 1,000 properties are directly linked to what financial regulators commonly call ‘politically exposed persons’, he says, and the true number is probably far higher.

“Many of these people might find it difficult to explain their wealth. They don’t necessarily have a vast private fortune to go along with their job positions, yet they buy multi-million-pound properties in central London.”

The Cambridge dictionary defines kleptocracy as “a society whose leaders make themselves rich and powerful by stealing from the rest of the people”. It sounds a little bit like the definition of corruption so why not just call it the ‘corruption tour’? “Because kleptocracy is not corruption,” says Oliver Bullough, journalist and author of The Last Man in Russia. “Corruption has existed as long as there have been officials. Kleptocracy, however, has been around probably since the 1960s, when people started using the word with the sense we give to it today.”

Dark side of globalisation

The phenomenon is characterised by three elements, he says: stealing, a corollary of corruption; obscuring, whereby the origin of the money is disguised by laundering it; and spending - on expensive cars, yachts, private jets and, of course, property.

In that regard, if kleptocracy is “the dark side of globalisation”, London is very much the Death Star.

“London is a real problem,” admits Bullough. “What makes London so special is that unlike remote places such as the British Virgin Islands, here you can obscure your money with the network of overseas territories and Crown dependencies and, most importantly, you can spend it, with all the beautiful things that are for sale in our wonderful capital.”

With perfect timing, we make the first stop on the tour, pulling up outside a six-bedroom house in one of London’s flashiest streets in the heart of Belgravia. It was bought by a Nigerian politician for £4.5m just a few years ago and is now worth around £13m.

Around the corner sits another property, a four-floor house allegedly owned by the same person, the operative word being “allegedly” because it is almost impossible to know for sure who is hiding behind a shell company registered in an offshore jurisdiction. You can’t follow the money unless something like the Panama Papers shows who the ultimate beneficial owner of these structures is.

Next up we head to Marylebone to the mansion of another senior figure, and so on, from Hyde Park to South Kensington, passing through all sorts of chic postcodes - SW1, W1, NW1 - taking notes of the names of presidents, senators, ministers and generals. Like the value of these properties, the amount of information is enormous.

This is because Nigeria is the richest country in Africa as well as one of the poorest. It is also one of the most corrupt countries in the world. According to research organisation Global Financial Integrity, between 2004 and 2013 an estimated $178bn (£135bn) of illicit financial flows left the country.

Some of those billions have flowed through offshore companies into London. “It’s like having an overflowing toilet,” says Matthew Page, author of the book Nigeria: What Everyone Needs to Know. “The government can’t just jiggle the handle and hope it will stop. A more holistic and durable solution is needed.”

Capital attraction

Until last year, Page was a Nigeria analyst at the US State Department, where he had been working for 14 years. He is now a consultant on military corruption issues for a number of NGOs, including Transparency International (TI). “London is one of the most attractive financial destinations for Nigerian elites,” he says. “Today we’re looking just at a small fraction of politically exposed people. Still, many of them have properties in London.”

Of course, it is not just Nigerian money that is looking for a home in London. The scale of offshore ownership of London real estate is probably unrivalled anywhere else in the world. In its report, London Property: A Top Destination For Money Launderers, TI estimates that at least 40,000 properties in the capital are owned by an offshore entity.

London is one of the most attractive financial destinations for Nigerian elites - Matthew Page, author

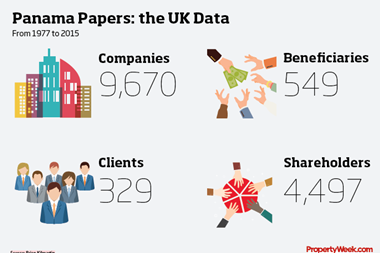

Although it is perfectly legal to own an offshore company, it is equally true that these structures might also be used, as the leaked Panama Papers have shown, for illicit purposes.

According to the National Crime Agency, about £100bn of illicit capital passes through London every year (that’s 12% of all the stolen capital in the world). Property is an easy target for criminals who need to launder big sums through assets with a high monetary value.

“We can’t do much about corruption, which is endemic to many countries, including Nigeria,” says Bullough. “But we can do something about kleptocracy.”

This is the purpose of the kleptocracy tours.

By exposing these properties, Borisovich and his unusual tour guides hope to dissuade others from stashing their dirty money in the UK.

“We’re calling on the government to stick to its promises on transparency,” says Borisovich. “At the anti-corruption summit, the last government issued a number of commitments that have been stalled with the new executive.”

Ghost towns

Rachel Davies Teka, head of advocacy at TI UK, believes that the rules need to be changed. “You can now easily set up an overseas company in a secrecy jurisdiction, buy a house in London and you don’t have to tell the Land Registry who you are,” she says. “The government said it was going to change this and that legislation would be introduced through parliament by April 2018.”

However, Davies Teka says that the government is almost certainly going to miss its own deadline. The upshot is that offshore-registered entities will continue to regard London as a safe haven and buy real estate there.

The amount of Nigerian money coming into the capital is a case in point. It has effectively created a ‘Nigerian quarter’ within posh neighbourhoods such as Maida Vale, St John’s Wood and Marylebone. However, far from resembling a ‘little Abuja’, as you would imagine, they are ghost towns. In fact, most of the properties we visit are not lived in.

While we are standing in front of one house in Maida Vale, the vicar from the local church comes by asking what we are doing. “That’s funny,” he says, when we tell him. “I’ve been here for 15 years and I’ve never seen anyone in that house.”

In short, kleptocracy is directly contributing to the ‘lights out London’ problem. Foreign buyers even have their own technical term to describe such properties: ‘buy-to-leave’.

“Houses have literally been turned into retirement savings boxes for foreign kleptocrats,” says Page. “All these empty multi-million‑pound houses within London’s most expensive neighbourhoods are just metres away from places where low-income Londoners live in neglected conditions. And obviously we had the Grenfell Tower disaster, which shows just how stark this juxtaposition is.”

Professional enablers

It is too easy to blame offshore companies and foreign capital for some of the issues blighting the London property market.

However, as one of the other journalists on the tour points out, these individuals need help buying UK assets, and this is where a number of sectors, including real estate, need to take a long hard look at themselves.

“There is a lucrative industry, here in the UK, which makes this possible,” says Christian Eriksson, investigative journalist at Private Eye. “They enable this game while making profit off the flow of dirty money.”

Eriksson describes them as ‘professional enablers’: bankers, lawyers and estate agents who facilitate the transactions. Until the rules are tightened, the klepto tour guides say, dirty money will continue to flood into the UK.

What we really need are anti-kleptocracy Jedis that can fight against the evil that is kleptocracy - Oliver Bullough, journalist and author

“We can stop that if we want to,” says Bullough. “What we really badly need are Jedi knights, anti-kleptocracy Jedis that can fight against the evil that is kleptocracy.”

At one point, towards the end of the tour, the bus takes a sharp bend and we find ourselves on the M25. All of a sudden the black skeletal frame of Grenfell Tower appears on the horizon.

The photographers on board jump out of their seats to take pictures of that devastating scene. Everyone else stays seated in silent contemplation.

Soon enough, however, the bus heads towards the centre of the capital and the shiny towers of the City’s skyline welcome us with their crooked-teeth smile. We are back on the dark side.

No comments yet