By Jonathan Goldstein, chief executive of Cain International

I was amazed to read recently that a school district in Mississippi had removed To Kill a Mockingbird from its pupils’ reading list because the book was making children “uncomfortable”.

Harper Lee’s masterpiece was a favourite of mine growing up. As James LaRue of the American Library Association said in objection to the removal, it “makes us uncomfortable because it talks about things that matter”.

The book is a classic precisely because of its challenging nature: it examines issues of race and persecution, encouraging people to look at things from other points of view.

In an international climate where major powers are increasingly pursuing protectionist, inward-looking, ‘anti-political correctness’ policies and the perspectives of others are often disregarded, it is disappointing but perhaps unsurprising that To Kill a Mockingbird has fallen out of favour.

The irony is that international politics, rather than Pulitzer Prize-winning literature, is what is making many of us feel uncomfortable. In the UK particularly, other people’s opinions seem to be forgotten as politicians act as though the referendum vote was 100:0, not 52:48.

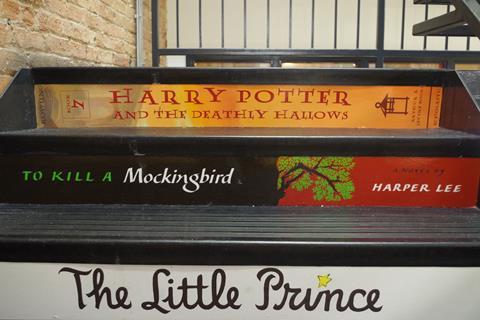

We have to take a leaf out of Harper Lee’s book and look at Brexit from both parties’ perspectives - Source: Flickr/Smart Chicago Collaborative/Creative Commons

Furthermore, the precise nature of what Britain will look like in March 2019 matters greatly but seems too uncomfortable a subject to be discussed in any detail.

Uncertainty is, and always has been, bad for business. In property particularly, where commercial leases last an average of seven years and developments can take a decade or more to come to fruition, 2019 is tomorrow. Companies already need to make decisions that will have consequences lasting far beyond our EU exit.

The government is trying to give an impression that everything is under control, but we appear little closer to a deal now than when the referendum result was first announced. With six months required at the end of the negotiations to get the deal through domestic and European parliaments, Brexit has become a ticking time bomb.

The clock is ticking

With every passing day, it is becoming more likely we will face a stark choice between going back into the EU on our previous terms - assuming they are still available - and leaving with no deal.

The uncomfortable element is that no one really knows what a no-deal Brexit means. From residency rights disappearing to tariffs being imposed on goods the UK sends to the EU, and vice versa, a no-deal situation with little preparation could be exactly the cliff edge we have been promised will be avoided.

A government white paper on customs has set out options for a no-deal scenario, with HMRC estimating that about 130,000 businesses that export to the EU would be dealing with customs for the first time. The UK would also cease to be a member of dozens of regulatory agencies, needing to set up new ones - a process that should have already started if it was to be completed in time.

Yet the government is reacting with empty statements. Boris Johnson’s resurrection of the ‘£350m-a-week-for-the-NHS’ fantasy and Chris Grayling’s reaction to Sainsbury’s chairman’s comments that a no-deal Brexit could result in an average 22% tariff on all EU food bought by British retailers are cases in point.

Grayling’s assertion that we will grow more food here was quickly disputed by the National Farmers’ Union, which said that if the country relied only on home-grown produce, cupboards would be bare in about seven months.

In short, Brexit is looking increasingly messy and the people upon whom we are relying to sort it out are providing no information about what the future holds. Time is running out. We need Theresa May to be decisive, present her party with realistic options and see if it will favour pragmatism or dogma. We have to take a leaf out of Harper Lee’s book and look at Brexit from both parties’ perspectives, however uncomfortable it may make us. It is no longer about being a Brexiteer or a Remoaner, but about getting the best possible deal for Britain.

No comments yet